Why aren’t all managers great?

Sep 09, 2024Written by Ed Cook

With the amount of energy that organizations put into the development of management skills, you might expect that most managers are great. Yet Gallup’s research shows that great managers are rare. A stunning 82% of the time, companies hire the wrong person to be a manager. Gallup’s latest State of the Global Workplace report suggests this repeated miss may be a cause for employees’ chronically low engagement at work with 33% reporting they are engaged in the US. Sadly, this is very high compared to the worldwide value of 23% who are engaged. Lest we immediately go to causes outside the manager, Gallup’s research has shown that 70% of the variation in the engagement score is attributable to the manager. As is sometimes true in research about the workplace, statistical analysis shows us what we already know: A poor manager leads to low employee engagement. Why is it so hard to find or create great managers?

What makes a great manager?

Those who are considered great managers often exhibit the same attributes. Again science finds what many already know, yet verifying our intuition is always valuable. Gallup highlights the following attributes of a great manager:

- They motivate employees to take action.

- They engage employees with a compelling mission and vision.

- They have the assertiveness to drive outcomes.

- They overcome adversity and resistance.

- They create a culture of clear accountability.

- They build relationships that create trust, open dialogue, and full transparency.

- They make decisions based on productivity, not politics.

Those of you who have even a passing understanding of our efforts to grow Joy at Work will recognize some of the 10 Dimensions of Joy at Work in the above list: accountability, trust, taking action (participation), compelling mission (commitment), and overcoming adversity (growth). What Gallup calls the manager’s contribution to engagement, we call Joy at Work.

It is the last attribute of a great manager “They make decisions based on productivity, no politics,” which steps away from the attributes of the manager and points to the structure of the organization. Certainly, a manager with high integrity (another dimension of Joy at Work) can push past the organizational culture (in this instance meaning incentives, messages, and processes) and make a decision based on productivity and not politics, but it is much harder to do so if the organizational culture rewards politics.

Work versus Workers

The word “politics” can be a trigger for immediate rejection of whatever is said next. Who would readily admit that they play politics at work? Yet, ask about a decision where a manager sacrificed employee engagement in favor of getting the work done, and the manager will likely reply something to the effect of, “Well, we just had to get that work done.” In isolation, each one of those decisions can readily be argued as correct, but is that still true in the aggregate? If every decision is one where the worker is sacrificed for the work, then some other mechanism is in place. If it is not politics, then what is it?

Perhaps it can be found in Gallup’s striking assertion that only 1 in 10 managers possess the necessary attributes. With coaching, companies can move that number to 2 in 10 (about 18%). They find that companies that do that improve their profits by 48%. Further, Gallup has found that companies that can increase the number of effective managers who can double the rate of employee engagement (to a still disappointing 66%) increase their earnings by a whopping 147%. So why don’t all companies do that?

Again, we don’t need science to tell us the answer we already know. It’s hard to do! But clearly, not impossible. Some companies are doing it. Even if you find the magnitude of the improvement unbelievable or wonder at the variation of results across different groups, there seems to be a significant effect. That should be enough to prompt some careful conversations about how to implement a process of improving both the selection of managers and the development of management capability.

A Modest Proposal for Change

It seems then that an organization needs two things in place to reap the benefits of a great manager. First, they need to put people with the attributes of a great manager into the role. Second, they need to reduce the incentives to sacrifice workers in favor of the work and increase the incentives to exhibit their skills as a great manager.

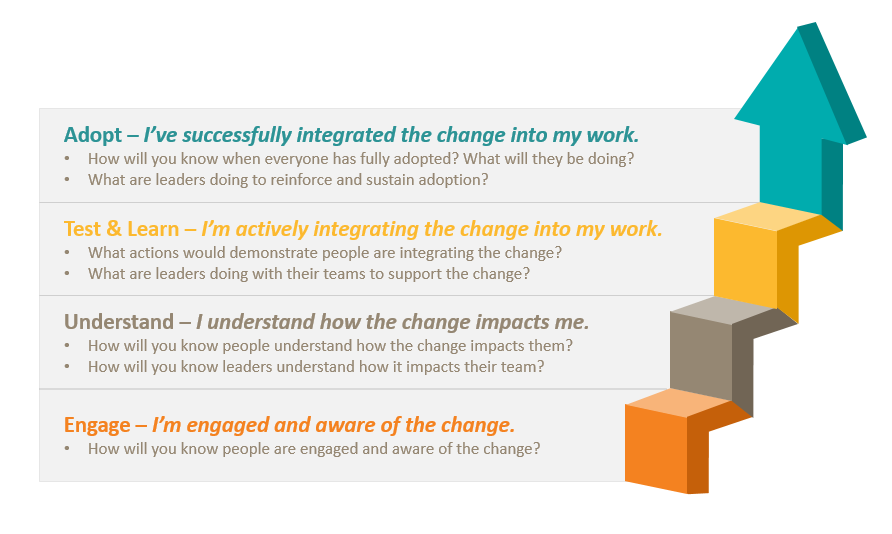

Since this is a change, we would suggest applying our four phases of change as a way to break down the change and know if you are making any progress. The crux of the model is asking questions that allow you to know if progress has occurred toward the change goal. So what is the change goal? We would suggest something simple, what we call a Leadership Intention. The leader of the organization needs to declare an intention for managers in their organization to be great. Something like this:

Our long-term success as an organization will come when our employees have great managers.

There is significant power in such a simple statement. The change model can now help because the questions under each of the four steps will have meaning. For example, the Engage statement “How will you know people are engaged and aware of the change?” can drive better thinking on what would need to occur for the change process to begin. Perhaps recruiting sees this and begins exploring different ways to vet future managers. Current leaders may begin talking about new ways of supporting rookie managers. The specifics, of course, will matter, but organizations may struggle to get to the specifics of the change without a goal and a framework on how to think about the goal. We hope this goal and this framework can contribute.